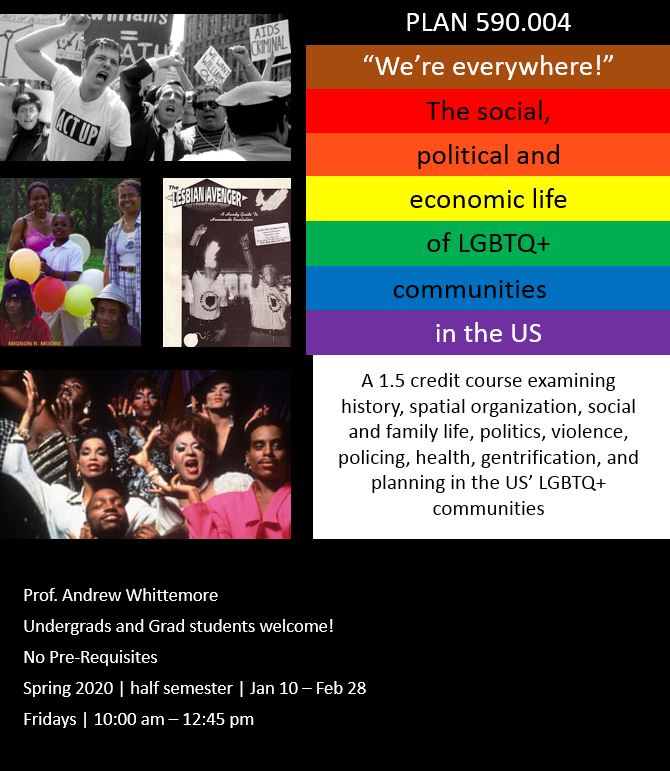

“We’re Everywhere!”: The Social, Political and Economic Life of LGBTQ+ Communities.

Since the end of the Second World War, if not before, more and more cities of the United States have come to feature spaces identified by members of LGBTQ communities and their heterosexual, cis-gendered counterparts as gay, lesbian, or queer. These have included intimate networks of homes, public spaces of all sizes, skid rows, commercial districts, residential urban neighborhoods, suburbs, small towns, some rural areas, and perhaps even entire cities.

LGBTQ-identified spaces have been key in the development of LGBTQ identity: they provide sites for socializing and socialization, organization, self-affirmation and expression, visibility, and for many even political empowerment and the accumulation of material wealth. They have also provided targets for violence, exploitation, and state suppression, and been exclusive of many LGBTQ-identifying people because of their racial, class, sexual, or gender identity.

This course, taught by Andrew Whittemore, introduces students to the social, political, and economic life of LGBTQ spaces in the United States, and asks students to consider their importance and the merits of planning for their improvement and/or conservation.

Urban planning has moved to different focuses over the years: health, simulation, poverty, and segregation. There may be a new area needed to be reviewed: gentrification and gayborhoods. LGBTQ gained a lot through visibility in various urban neighborhoods in the 20th century. The targeting of these neighborhoods with harassment by police and ordinary locals alike catalyzed the first political organizing that blossomed into the movements for LGBTQ rights that we know today. Yet planning for the most part treats these places as if they do not exist – overlooking how gentrification leads to the dispersion of LGBTQ people in US cities, and the challenges dispersion presents for LGBTQ populations: in political organizing, in accessing services, and in their social lives.

How did these LBGTQ spaces initially start to develop?

The theater and entertainment districts that coalesced in American cities during the 19th century provided the first spaces identified by both LGBTQ people and non-LGBTQ people as relatively safe spaces for non heteronormative or gender normative people. Times Square in New York City was one such place that had a vibrant LGBTQ life by the 1920s. But most of the places that came to be known as gayborhoods did not develop until after World War II, with the departure of large numbers of white straight-identified households from American cities. This left lots of cheap housing available in cities available for increasing populations of young single men and women of “the greatest generation,” many of whom had come to identify as homosexual when uprooted from their home towns over the course of World War II.

What effect did the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy during WWII have on these spaces?

This question is a little flawed – any revelation of same-sex sexual behavior between soldiers or other service members during world war II would have immediately led to a dishonorable discharge in nearly all circumstances. Don’t Ask Don’t Tell was instituted in the mid-90s as a way of saying that people who identified as homosexual would be tolerated, as long as they kept that identification strictly private.

What effect did the 2000 Census have on the LBGTQ community?

Not until the 2000 Census did the LBGTQ community have a section, or clarification of their sexual orientation on the form. But the census only way of identifies LGBTQ people is through identifying same-sex cohabiting couples, and a minority of LGBTQ people are part of and openly identify as part of such couples.

How are the LGBTQ community needs different from other groups? How can the planning process be smoother?

Michael Frisch (2002) expresses that there is the domination of the heterosexual community and suppression of homosexuality in planning in his article Planning as a Heterosexist Project (p. 256). This could be the reason that the LGBTQ community is being seen the same as other minority in the planning process since planning is “built around heterosexual constructs of family, work, and community.” See my answer above – LGBTQ populations are usually just ignored by planners altogether. Some things, like affordable housing, would benefit LGBTQ people but also many other sorts of people. Other things, like stricter enforcement so-called “quality-of-life measures” (i.e. zero tolerance for loitering, noise, other things perhaps perceived as nuisances by some) may disproportionately harm some sectors of the LGBTQ population while benefiting local homeowners, many of whom might also be LGBTQ (but likely white gay cis males). It’s complicated.

How has the APA responded to support this community?

The American Planning Association (APA) is aware of these gaps in planning for these communities. APA has had an informal group for planners apart and support the LGBTQ community since 1992. Today, they have The Gays and Lesbians in Planning (GALIP) Division of APA since 1998 which is “a forum for the exchange of ideas and information of interest to gays, lesbians, and friends in the planning profession” (APA, 2017).

_____________________________________________________________________________

About the instructor:

About the instructor:

Andrew H. Whittemore

Assistant Professor; Director of Undergraduate Studies

Specialization: Land Use and Environmental Planning

Dr. Whittemore’s research focuses on urban form, planning history, planning theory, land use planning, and zoning, primarily in the United States. He especially focuses on zoning’s influence on the built form of US cities and the politics associated with zoning decisions. He principally uses archival and ethnographic methods to explore questions about why local communities make the zoning decisions they do. He has published on the history of zoning and land use politics in Los Angeles, the FHA’s impact on local zoning, redevelopment politics in conservative contexts, the uses and politics of planned unit development, the role of racial bias in zoning decisions, the history of American urban form, and planning theory with a focus on phenomenological or humanist procedural approaches to planning.

About the course:

PLAN 573 “WE’RE EVERYWHERE!”: THE SOCIAL, POLITICAL AND ECONOMIC LIFE OF LGBTQ+ COMMUNITIES [Note: This course number will be changed to PLAN 573, but for spring 2021 it is currently being scheduled as PLAN 590.001]

Title: “We’re Everywhere!”: The Social, Political and Economic Life of LGBTQ+ Communities

Description: Since the end of the Second World War, if not before, more and more cities of the United States have come to feature spaces identified by members of LGBTQ communities and their heterosexual, cis-gendered counterparts as gay, lesbian, or queer. These have included intimate networks of homes, public spaces of all sizes, skid rows, commercial districts, residential urban neighborhoods, suburbs, small towns, some rural areas, and perhaps even entire cities. LGBTQ-identified spaces have been key in the development of LGBTQ identity: they provide sites for socializing and socialization, organization, self-affirmation and expression, visibility, and for many even political empowerment and the accumulation of material wealth. They have also provided targets for violence, exploitation, and state suppression, and been exclusive of many LGBTQ-identifying people because of their racial, class, sexual, or gender identity. This class introduces students to the social, political, and economic life of LGBTQ spaces in the United States, and asks students to consider their importance and the merits of planning for their improvement and/or conservation. No pre-requisites, open to undergraduate and graduate students.